Introduction

Object-Oriented Programming, also known as OOPs concepts in Python. In this article, I will explain the basic concepts of Object-Oriented Programming in Python programming, oop fundamentals, and features of oops.

Developers often choose to use OOP concepts in Python programs because it makes code more reusable and easier to work with larger programs. OOP programs prevent you from repeating code because a class can be defined once and reused many times.

Table of Contents

What Is Object-Oriented Programming?

Object-Oriented Programming(OOP), a programming paradigm, is all about creating “objects.” An object is a group of interrelated variables and functions. These variables are often referred to as properties of the object, and functions are referred to as the behaviour of the objects. These objects provide a better and clear structure for the program.

For example, a car can be an object. If we consider the car as an object, its properties would be its color, model, price, brand, etc. And its behaviour/function would be acceleration, slowing down, and gear change.

Another example – If we consider a dog as an object then its properties would be its color, breed, name, weight, etc., and its behaviour/function would be walking, barking, playing, etc.

Object-Oriented Programming is famous because it implements real-world entities like objects, hiding, inheritance, etc, in programming. It makes visualization easier because it is close to real-world scenarios.

Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) vs Procedure Oriented Programming (POP)

The basic differences between OOP and POP are the following:

One way to think about POP is the same way you make lemonade, for example. The procedure of making lemonade involves- first taking water according to the need, then adding sugar to the water, then adding lemon juice to the mixture, and finally mixing the whole solution. And your lemonade is ready to serve. Similarly, POP requires a certain procedure of steps. A procedural program consists of functions. This means that in the POP approach, the program is divided into functions that are specific to different tasks. These functions are arranged in a specific sequence, and the control of the program flows sequentially.

On the other hand, an OOP program consists of objects. The object-oriented approach divides the program into objects. And these objects are the entities that bundle up the properties and the behaviour of real-world objects.POP is suitable for small tasks only. Because as the program’s length increases, the code’s complexity also increases. And it ends up becoming a web of functions. Also, it becomes hard to debug. OOP solves this problem with the help of a clearer and less complex structure. It allows code re-usability in the form of inheritance.

Another important thing is that in procedure-oriented programming, all the functions have access to all the data, which implies a lack of security. Suppose you want to secure the credentials or any other critical information from the world. Then the procedural approach fails to provide you with that security. For this OOP helps you with one of its amazing functionality known as Encapsulation, which allows us to hide data. Don’t worry I’ll cover this in detail in the latter part of this article along with other concepts of Object-Oriented Programming. For now, just understand that OOP enables security and POP does not.

Programming languages like C, Pascal, and BASIC use the procedural approach, whereas Java, Python, JavaScript, PHP, Scala, and C++ are the main languages that provide the Object-oriented approach.

Major OOPs Concepts in Python

In this section, we will dive deep into the basic concepts of OOP, covering topics such as class, object, method, inheritance, encapsulation, polymorphism, and data abstraction.

What Is a Class?

A straightforward answer to this question is- A class is a collection of objects. Unlike primitive data structures, classes are data structures that the user defines. They make the code more manageable.

Let’s see how to define a class below-

class class_name:

class body

We define a new class with the keyword “class” following the class_name and colon. And we consider everything you write under this after using indentation as its body. To make this more understandable, let’s see an example.

Consider the case of a car showroom. You want to store the details of each car. Let’s start by defining a class first-

class Car:

pass

That’s it!

Note: I’ve used the pass statement in place of its body because the main aim was to show how you can define a class and not what it should contain.

Even the datatypes in Python, like tuples, dictionaries, etc. are classes.

Before going into detail, first, understand objects and instantiation.

Objects and Object Instantiation

When we define a class, only the description or a blueprint of the object is created. There is no memory allocation until we create its object. The objector instance contains real data or information.

Instantiation is nothing but creating a new object/instance of a class. Let’s create the object of the above class we defined-

obj1 = Car()

And it’s done! Note that you can change the object name according to your choice.

Try printing this object-

print(obj1)

<main.Car object at 0x000002036C872640>

Since our class was empty, it returns the address where the object is stored i.e. 0x000002036C872640

You also need to understand the class constructor before moving forward.

Class Constructor

Until now, we have had an empty class Car, time to fill up our class with the properties of the car. The job of the class constructor is to assign the values to the data members of the class when an object of the class is created.

There can be various properties of a car, such as its name, color, model, brand name, engine power, weight, price, etc. We’ll choose only a few for understanding purposes.

class Car:

def __init__(self, name, color):

self.name = name

self.color = color

So, the properties of the car or any other object must be inside a method that we call init( ). This init() method is also known as the constructor method. We call a constructor method whenever an object of the class is constructed.

Now let’s talk about the parameter of the init() method. So, the first parameter of this method has to be self. Then only will the rest of the parameters come.

The two statements inside the constructor method are –

self.name = name

self.color = color

This will create new attributes, namely name and color, and then assign the value of the respective parameters to them. The “self” keyword represents the instance of the class. By using the “self” keyword, we can access the attributes and methods of the class. It is useful in method definitions and variable initialization. The “self” is explicitly used every time we define a method.

Note: You can also create attributes outside of this init() method. But those attributes will be universal to the whole class, and you will have to assign a value to them.

Suppose all the cars in your showroom are Sedan, and instead of specifying it again and again, you can fix the value of car_type as Sedan by creating an attribute outside the init().

class Car:

car_type = "Sedan" #class attribute

def __init__(self, name, color):

self.name = name #instance attribute

self.color = color #instance attribute

Here, Instance attributes refer to the attributes inside the constructor method, i.e., self.name and self.color. And Class attributes refer to the attributes outside the constructor method, i.e., car_type.

Class Methods

So far, we’ve added the properties of the car. Now it’s time to add some behaviour. Methods are the functions we use to describe the behaviour of objects. They are also defined inside a class. Look at the following code-

Python Code:

class Car:

car_type = "Sedan"

def __init__(self, name, mileage):

self.name = name

self.mileage = mileage

def description(self):

return f"The {self.name} car gives the mileage of {self.mileage}km/l"

def max_speed(self, speed):

return f"The {self.name} runs at the maximum speed of {speed}km/hr"

obj2 = Car("Honda City",24.1)

print(obj2.description())

print(obj2.max_speed(150))

The methods defined inside a class other than the constructor method are known as the instance methods. Furthermore, we have two instance methods here – description() and max_speed(). Let’s talk about them individually:

description()- This method returns a string with the description of the car, such as the name and its mileage. This method has no additional parameter. This method uses instance attributes.

max_speed()- This method has one additional parameter and returns a string displaying the car’s name and speed.

Notice that the additional parameter speed is not using the “self” keyword. Since speed is not an instance variable, we don’t use the self keyword as its prefix. Let’s create an object for the class described above.

obj2 = Car("Honda City",24.1)

print(obj2.description())

print(obj2.max_speed(150))

The Honda City car gives a mileage of 24.1km/l

The Honda City runs at a maximum speed of 150km/hr

What we did was we created an object of class car and passed the required arguments. To access the instance methods, we use object_name.method_name().

The method description() didn’t have any additional parameter, so we did not pass any argument while calling it.

The method max_speed() has one additional parameter, so we passed one argument while calling it.

Note: Three important things to remember are-

You can create any number of objects in a class.

If the method requires n parameters and you do not pass the same number of arguments, then an error will occur.

The order of the arguments matters.

Let’s look at these, one by one:

Creating more than one object of a class

class Car:

def __init__(self, name, mileage):

self.name = name

self.mileage = mileage

def max_speed(self, speed):

return f"The {self.name} runs at the maximum speed of {speed}km/hr"

Honda = Car("Honda City",21.4)

print(Honda.max_speed(150))

Skoda = Car("Skoda Octavia",13)

print(Skoda.max_speed(210))

The Honda City runs at a maximum speed of 150km/hr

The Skoda Octavia runs at a maximum speed of 210km/hr

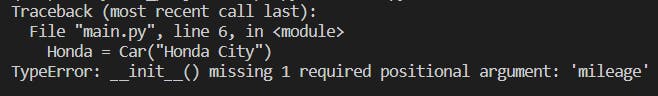

Passing the wrong number of arguments

class Car:

def __init__(self, name, mileage):

self.name = name

self.mileage = mileage

Honda = Car("Honda City")

print(Honda)

Since we did not provide the second argument, we got this error.

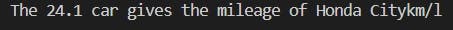

Order of the arguments

class Car:

def __init__(self, name, mileage):

self.name = name

self.mileage = mileage

def description(self):

return f"The {self.name} car gives the mileage of {self.mileage}km/l"

Honda = Car(24.1,"Honda City")

print(Honda.description())

Messed up! Notice we changed the order of arguments.

There are four fundamental concepts of Object-oriented programming – Inheritance, Encapsulation, Polymorphism, and Data abstraction. It is essential to know about all of these in order to understand OOPs. Till now, we’ve covered the basics of OOPs concepts in python; let’s dive in further.

Inheritance in Python Class

Inheritance is the procedure in which one class inherits the attributes and methods of another class. The class whose properties and methods are inherited is known as the Parent class. And the class that inherits the properties from the parent class is the Child class.

The interesting thing is, along with the inherited properties and methods, a child class can have its own properties and methods.

How to inherit a parent class? Use the following syntax:

class parent_class:

body of parent class

class child_class( parent_class):

body of child class

Let’s see the implementation:

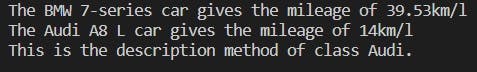

class Car: #parent class

def __init__(self, name, mileage):

self.name = name

self.mileage = mileage

def description(self):

return f"The {self.name} car gives the mileage of {self.mileage}km/l"

class BMW(Car): #child class

pass

class Audi(Car): #child class

def audi_desc(self):

return "This is the description method of class Audi."

obj1 = BMW("BMW 7-series",39.53)

print(obj1.description())

obj2 = Audi("Audi A8 L",14)

print(obj2.description())

print(obj2.audi_desc())

We have created two child classes, namely “BMW” and “Audi,” who have inherited the methods and properties of the parent class “Car.” We have provided no additional features and methods in the class BMW. Whereas one additional method inside the class Audi.

Notice how the instance method description() of the parent class is accessible by the objects of child classes with the help of obj1.description() and obj2.description(). The separate method of class Audi is also accessible using obj2.audi_desc().

Encapsulation

Encapsulation, as I mentioned in the initial part of the article, is a way to ensure security. It hides the data from the access of outsiders. Such as, if an organization wants to protect an object/information from unwanted access by clients or any unauthorized person, then encapsulation is the way to ensure this.

You can declare the methods or the attributes protected by using a single underscore ( ) before their names, such as self.name or def method( ); Both of these lines tell that the attribute and method are protected and should not be used outside the access of the class and sub-classes but can be accessed by class methods and objects.

Though Python uses ‘ _ ‘ just as a coding convention, it tells that you should use these attributes/methods within the scope of the class. But you can still access the variables and methods which are defined as protected, as usual.

Now to prevent the access of attributes/methods from outside the scope of a class, you can use “private members“. To declare the attributes/method as private members, use a double underscore ( ) in the prefix. Such as – **self.**name or def __method(); Both of these lines tell that the attribute and method are private and access is not possible from outside the class.

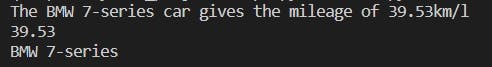

class car:

def __init__(self, name, mileage):

self._name = name #protected variable

self.mileage = mileage

def description(self):

return f"The {self._name} car gives the mileage of {self.mileage}km/l"

obj = car("BMW 7-series",39.53)

#accessing protected variable via class method

print(obj.description())

#accessing protected variable directly from outside

print(obj._name)

print(obj.mileage)

Notice how we accessed the protected variable without any error. It is clear that access to the variable is still public. Let us see how encapsulation works-

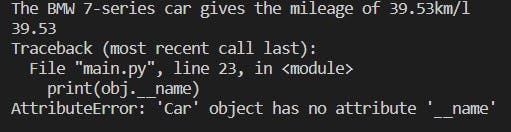

class Car:

def __init__(self, name, mileage):

self.__name = name #private variable

self.mileage = mileage

def description(self):

return f"The {self.__name} car gives the mileage of {self.mileage}km/l"

obj = Car("BMW 7-series",39.53)

#accessing private variable via class method

print(obj.description())

#accessing private variable directly from outside

print(obj.mileage)

print(obj.__name)

When we tried accessing the private variable using the description() method, we encountered no error. But when we tried accessing the private variable directly outside the class, then Python gave us an error stating: the car object has no attribute ‘__name’.

You can still access this attribute directly using its mangled name. Name mangling is a mechanism we use for accessing class members from outside. The Python interpreter rewrites any identifier with “__var” as “_ClassName__var”. And using this you can access the class member from outside as well.

class Car:

def __init__(self, name, mileage):

self.__name = name #private variable

self.mileage = mileage

def description(self):

return f"The {self.__name} car gives the mileage of {self.mileage}km/l"

obj = Car("BMW 7-series",39.53)

#accessing private variable via class method

print(obj.description())

#accessing private variable directly from outside

print(obj.mileage)

print(obj._Car__name) #mangled name

Note that the mangling rule’s design mostly avoids accidents. But it is still possible to access or modify a variable that is considered private. This can even be useful in special circumstances, such as in the debugger.

Polymorphism

This is a Greek word. If we break the term Polymorphism, we get “poly”-many and “morph”-forms. So Polymorphism means having many forms. In OOP it refers to the functions having the same names but carrying different functionalities.

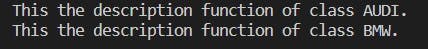

class Audi:

def description(self):

print("This the description function of class AUDI.")

class BMW:

def description(self):

print("This the description function of class BMW.")

audi = Audi()

bmw = BMW()

for car in (audi,bmw):

car.description()

When the function is called using the object audi then the function of class Audi is called, and when it is called using the object bmw, the function of class BMW is called.

Data Abstraction

We use Abstraction for hiding the internal details or implementations of a function and showing its functionalities only. This is similar to the way you know how to drive a car without knowing the background mechanism. Or you know how to turn on or off a light using a switch, but you don’t know what is happening behind the socket.

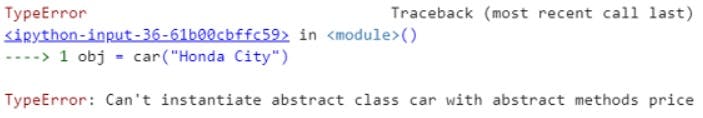

Any class with at least one abstract function is an abstract class. To create an abstraction class, first, you need to import the ABC class from abc module. This lets you create abstract methods inside it. ABC stands for Abstract Base Class.

from abc import ABC

class abs_class(ABC):

Body of the class

The important thing is – you cannot create an object for the abstract class with the abstract method. For example-

Now the question is, how do we use this abstraction exactly? The answer is, by using inheritance.

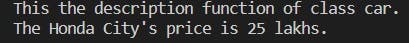

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class Car(ABC):

def __init__(self,name):

self.name = name

def description(self):

print("This the description function of class car.")

@abstractmethod

def price(self,x):

pass

class new(Car):

def price(self,x):

print(f"The {self.name}'s price is {x} lakhs.")

obj = new("Honda City")

obj.description()

obj.price(25)

Car is the abstract class that inherits from the ABC class from the abc module. Notice how I have an abstract method (price()) and a concrete method (description()) in the abstract class. This is because the abstract class can include both of these kinds of functions, but a normal class cannot. The other class inheriting from this abstract class is new(). This method defines the abstract method (price()), which is how we use abstract functions.

After the user creates objects from the new() class and invokes the price() method, the definitions for the price method inside the new() class comes into play. These definitions are hidden from the user. The Abstract method is just providing a declaration. The child classes need to provide the definition.

But when the description() method is called for the object of the new() class, i.e, obj, the Car’s description() method is invoked since it is not an abstract method.

Conclusion

We’ve now covered the basic concepts of Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) in this Python tutorial. In Python, object-oriented Programming (OOPs) is a programming paradigm that uses objects and classes in programming. OOPs, concepts in Python, aim to implement real-world entities like inheritance, polymorphisms, encapsulation, etc., in the programming.